Violet-green Swallow

General Description

Violet-green Swallows are small and sleek, iridescent violet-green above and white below. The sides of their heads are white, with the white extending above the eye. Their tails are moderately forked. The white of the undersides extends up the sides of the rump forming two white patches. In Washington, Violet-green Swallows are most likely to be confused with Tree Swallows, but Tree Swallows have no white above the eye and no white patches. On perched birds, the wings of Violet-green Swallows extend beyond the tail while those of Tree Swallows do not. Compared to males, females are drab in color. Juveniles are brownish-gray above with a grayish-white belly. They have dusky faces and lack the faint breast-band of the juvenile Tree Swallow.

Habitat

This western species is often associated with coniferous forests in mountainous areas, but in Washington it uses a variety of habitats. Young forests, clearcuts, prairies, wetlands, open water, and even cities are all used by Violet-green Swallows. This is the swallow most likely to be seen in urban areas within Washington's forested zones. Violet-green Swallows are often found at forest edges with large snags or other cavities for nesting. In late summer they are common at high elevations. During migration, they are often found near water, and in early spring, many remain near water and do not disperse to their breeding areas until the arrival of consistently warm weather.

Behavior

These social birds are often found in flocks of mixed-swallow species and in single-species flocks. They are highly acrobatic and forage almost exclusively in flight. Their flight is more fluttery than that of Tree Swallows, and they often fly higher than other swallow species. They will, however, feed low over open water, especially in bad weather.

Diet

Violet-green Swallows feed almost exclusively on flying insects.

Nesting

Violet-green Swallows nest in tree cavities, cliffs, buildings, old woodpecker holes, and nest boxes. Originally, they probably nested in rock crevices and tree holes, and although they now take advantage of man-made structures, they do not take as readily to nest boxes as do Tree Swallows. They nest in isolated pairs or small colonies of up to 25 nests. Both male and female build the nest, a cup of grass, twigs, rootlets, and straw, lined with feathers of other birds. The female incubates four to six eggs for 14 to 15 days. Both adults feed the young, which leave the nest after 23-24 days. The parents continue to feed the young for some time after they leave the nest.

Migration Status

Violet-green Swallows arrive early in spring, especially in eastern Washington, and are one of the first returning migrants. After a post-breeding migration to higher elevations, they leave for the winter. Some winter on the southern California coast, but most winter in Mexico and Central America. Two waves of migrants can often be detected, birds that have bred in Washington leaving the state in late July or early August and breeders from farther north (including many immature birds) passing through in late September. They migrate in flocks, often traveling along ridges and major rivers.

Conservation Status

Violet-green Swallows have increased significantly in Washington since 1966. They may have benefited from an increased supply of artificial nest boxes, although they must compete with European Starlings and House Sparrows for them. Their ability to use a variety of habitats and the fact that they can nest successfully in cities and towns should help the population remain stable.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Violet-green Swallows are common throughout Washington in appropriate habitats from mid-March to early September. In some places, including Yakima County, they return as early as late February. They are less common, but can still be seen, through the end of September. During fall migration, thousands collect in south-central Washington (Klickitat County).

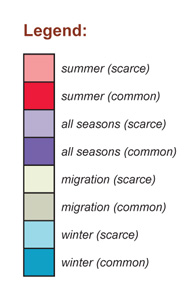

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | F | C | C | C | C | F | U | |||||

| Puget Trough | U | C | C | C | C | C | F | R | ||||

| North Cascades | U | C | C | C | C | F | U | R | ||||

| West Cascades | R | F | C | C | C | C | C | U | ||||

| East Cascades | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | |||||

| Okanogan | C | C | C | C | C | C | U | |||||

| Canadian Rockies | U | F | C | C | C | C | F | U | ||||

| Blue Mountains | R | U | U | U | U | U | U | |||||

| Columbia Plateau | F | C | C | C | C | C | F | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map